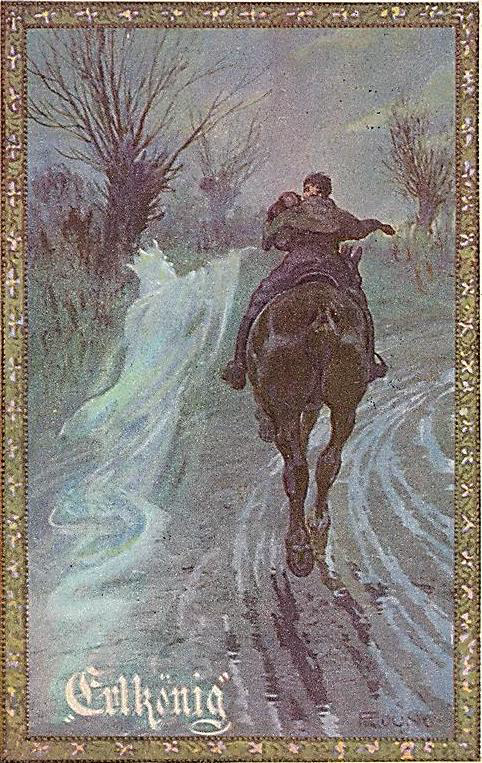

Who rides there so late through the night dark and drear? The father it is, with his infant so dear; He holdeth the boy tightly clasp’d in his arm, He holdeth him safely, he keepeth him warm. “My son, wherefore seek’st thou thy face thus to hide?” “Look, father, the Erl-King is close by our side! …. The father now gallops, with terror half wild, He grasps in his arms the poor shuddering child; He reaches his courtyard with toil and with dread, – The child in his arms finds he motionless, dead.

Recently I saw a fantastic theater play “The Erlkoenig”, which was a German adaptation of the movie “The Ice Storm” by the Taiwanese-born director Ang Lee. In the movie 1973, suburban Connecticut, middle class families experimenting with casual sex, drink and drugs find their lives out of control. Both scripts show frequent symbolism and formal movie pattern that Lee has described as cubist: “Many facets put together in a narrative way so that you can watch it from many angles and they all mean something. Products of 50s parents, these 70s traditional single-earner middle-class parents struggled with their Ego, their anima /animus, the coroporate rat race or their housewife boredom and with their children, found themselves confused as to the direction.

One facet of the movie pattern that Lee visualized is the children parent relationship of two befriended affluent families, both with one son and one daughter. Times have changed then already, and the fathers struggle almost more severe as their adolescent sons in the aftermath of the sexual revolution to find their true, authentic masculinity. So do mothers and daughters with their female role, deeply depressed and alianated with themselves.

The Film is based on Rick Moody’s 1994 novel about growing up in affluent New Canaan, Connecticut, during the last years of the cultural revolution of the West. Lee had initially envisioned a satirical comedy and the film script had, therefore, softened Moody’s ferocious revelation that he is Paul, the bright, somewhat confused son of Ben and Elena Hood of the book. Ben is no longer an alcoholic in the film script, and Elena appears rather snappier in the play or movie than socially aloof and icy old. Jim and Janey Carver, neighbors, with whom the Hoods become sexually entangled, offer also sharp portrayals of two lonely people in a failed marriage.

Now and Then

Most of the events of the film take place on Thanksgiving Day 1973 when the sexual, cultural, and political revolts that exploded in the late sixties reached the adult middle class. The theatre play moved those events to Germany during the Christmas Season 2017; roughly two years after Merkel had brought havoc to Germany and Europe by opening the borders. As the characters prepare to celebrate Christmas, Germany is already sliding onto the downward slope that will lead to the end of that heady era.

Alcohol and sex become escapes characteristic of 1970s middle class, as under Nixon the country became deeply divided, the 1973 gas crisis, the lingering Vietnam conflict, and economic recession cut deep into the nation’s self-esteem. Likewise today a German “Generation Snowflake” and their parent turn to the rat race, booze, and tranquilizers. Politically silenced and confused, but unconsciously unraveled and disgusted, they must cope with an economy in decline, loss of freedom, erratic crime and a future which promises only worse.

Every adult in the film and the theatre play embraces some drugs, usually appearing with a drink in their hands. Most of the principal adult characters also cope through sex with multiple partners—a condition that reaches its peak at the adult “key party,” invented in California in the 70’s where everyone in attendance drops their car keys in a bowl and goes home with whoever picks theirs out. In both worlds “manufactured consent” of the mainstream media and school indoctrination holds them in check, but show the first cracks. In Germany, its absurdity already reaches Orwellian dimensions and open political and social repression.

Lee, whose first three films were in Mandarin, arguably made the best American Indie film of the nineties. “The period portrayed in The Ice Storm is innocent and good because people are rebelling against old rules and the old order,” he has said. “The period portrayed in theater play named “The Erlkoenig” is doomed because its young generation is succumbing to imposed rules and order from the top. Lee continues; “We’re jaded now, while the people of that era were very fresh and bold about reaching their limits. What they encounter in the process is human nature, and the ice storm, which gives you a little more respect for nature. It turns out that we’re not that free after all.” Lee’s statement expresses — transformed into the presents(s) — its dark message: without some positive sense of the past, and the hunch, that the future is at best an empty promise the future might be exactly that.

Politicians on television are virtually an important character in the play (Merkel) as well as in the film (Richard Nixon). As Paul’s younger sister, Wendy recites Merkels and Nixon’s lies talking to her brother—she defines both time periods. The happy confluence of sexual freedom has changed in the play to childish girlie power and playful political revolution to heavy political regression from the top.

In 1997, some critics thought they recognized reactionary attitudes in The Ice Storm’s treatment of its unabashedly upper-middle-class, post-revolutionary subject matter. Indeed one thing that gives The Ice Storm and its German adaption both almost hallucinatory intensity is the fact, that both refer to a past and present Genocide: Wendy saying grace by thanking God “for letting us white people kill all the Indians and win in Vietnam” is echoed in the West today it seems, thanking self-destructive Evil “for letting us kill all white people”. In the play, Wendy saying grace “for letting us kill all Syrian people” and gives a reference to the holocaust. This reference is amplified by a rather lengthy additional scene.

Psychological dimension

The inner disturbance

A clever collage in the play with the poem “The Erlkoenig” from Goethe highlights one psychological dimension of Rick Moody’s novel, the relationship of fathers to their sons and their icy mothers. Likewise the antagonist in Goethe’s Erlkönig is, as the title suggests, the Erlking himself rather than mother or daughter he mentions in the ballad. Goethe’s Erlking’s motives are never made clear and is much more akin to the Germanic portrayal of elves and valkyries – a force of death rather than simply a magical spirit.

Already in the first verse, the words “night” and “wind” convey a cold, which is intensified by the probably fast ride. In the third and fourth verse this seems to counteract the father’s warm support. In the second stanza comes with the fog another climatic condition, which underlines the cold temperature again. The fear is triggered by the threatening nature: The fact that nature, with its sublime metamorphoses as such, attracts and repels people as well as awakens adolence longing and horror, has been expressed in a popularized form by Goethe with his ballad. The boy’s fear of the uncanny, threatening nature in the personification of the Erlkoenig forms the center of the lyric-epic-dramatic interpretation of The Ice Rain.

“You see the elf-king, father?

He’s near! The king of the elves with crown and train!”

“My son, the mist is on the plain.”

‘Sweet lad, o come and join me, do!

Such pretty games I will play with you;

On the shore gay flowers their color unfold,

My mother has many garments of gold

One of myassociation are fragments of Goethe’s poetry snd Rick Moody’s novel with Jung’s Red Book. Jung made once a remark about his Red Book: „archetypes speak the language of high rhetoric, even of bombast. (…) “ The two most important archetypes, who accompanied him in his dream wanderings are the Wise Old Man (Elijah, then Philemon) and the girl Salome (his Anima). The employment of these and to other figures of his dreams and awake imagination led him to the deciding insight, namely that there are things in the psyche which avoid our control, show themselves and develop an own way of sometimes scary life. One has to recognize and accept that Anima and Animus is irrational. Anima and Animus is the first internal God you meet. Dreams are the knowledge of the heart.

The outer disturbance

If you are boys, your God is a woman.

If you are women, your God is a boy.

If you are men, your God is a maiden.

The Red Book has been characterized according do the New York Times variously as a creative psychosis, a descent into the underworld, a plunge in insanity, a narcissistic self-deification, a transcendence experience, a midlife crisis and an inner disturbance foreseeing the upheaval of World War I and afterwards.

Likewise most interpretations of the poem see the Erlkoenig as a mere spawn of fear and as an expression of the boy’s unknown struggle with the female (his anima), which kills him at the end of the ballad in the arms of his helpless father.

Some interpreters criticize the careless attitude of the father in the poem against rationally incomprehensible evil powers. As some verses, such as “You dear child, come with me!” Or “And if you are not willing, then I need violence “, reminiscent of cases of abuse of children, some interpreters tend to think that the poem is about a sexual abuse. It may very wll be also about insuffucient fathers not being authentic role models, failing to break their sons free of their mothêr or of abusive mother archetypes. There are clearly parallels to characters in Rick Moody’s 1994 novel.

The odd situation of parents imitating styles set by a generation only slightly older than the children they are struggling to raise, is even more obvious today, in the desperate attempt to be their children’s peers rather than adults. On the one hand, the play suggests the old saw “Like father, like son”: Ben and Paul both pry into other people’s medicine cabinets, for example, and neither of them can take advantage of opportunities for sex that presents them the night of the storm. But “Like daughter, like the mother” also applies: Elena imitates Wendy’s bike riding and Wendy her rather futile approach to sex.

This all reflects Moody’s narrative: “Though metaphors of the mind of God are characterized by coincidence and repetition, examples from nature aren’t as tidy. Nature is senseless and violent.” So is history, so is reality one might add. Which brings us to the ice storm an Erlkönig, a metaphor for the movie respective the play and their titles; “When I think of The Ice Storm, I think first of water and rain, of how it falls everywhere, seeps into everything, forms underground rivers, and helps to shape a landscape,” writes Lee in his preface to the published screenplay. “And also, when calm, of how it forms a reflective surface, like glass, in which the world reappears. Then, as the temperature drops, what was only water freezes. Its structure can push iron away, it is so strong. Its pattern overthrows everything.”

The End

The movie ends tragically for Mikey the dreamer; he gets electrocuted in the ice storm. Ben Hood finds him and carries him to his house. Later Mikey’s father Jim Williams discovers his son is dead. Pronounced father-son relationship are not visible in the play, which he might have needed in order to face reality. It does not matter where in this world you live. It does not matter if you are successful or rich. In the end, Jim Carver grieves over his dead son. He has already lost his wife Janey Carver long time ago, as she did lose herself. As Paul comes home from a pot party, his father Ben and younger sister Wendy take him relieve in their arms and mother Elena Hood joins in. Family matters.

The original novel and the movie does end on a somewhat darker note. They hint in a last scene, when the whole family picks up Paul at the the train station with relief, that nothing really changed with the Hoods. Nor did anything get better with the Williams.

“Three things make people want to change. One is that they hurt sufficiently. They want to change. Another thing that makes people want to change is a slow type of despair called ennui, or boredom. This is what the person has who goes through life saying, “So what?” until he finally asks the ultimate big “So What?” They are ready to change. A third thing that makes people want to change is the sudden discovery that they can.

Personal resonance

Neither, pain nor boredom gave the two families enough momentum to change their lives. “Everyone strives after the law,” says the man afraid to go through the door in Franz Kafka’s novel, “so how is that in these many years no one except me has requested entry?” The gatekeeper sees that the man is already dying and, in order to reach his diminishing sense of hearing, he shouts at him, “Here no one else can gain entry since this entrance was assigned only to you. I’m going now to close it.

Rick Moody’s 1994 novel provides one reason why the 90s produced parents detached from their children and the 2010s people often don’t bother with children at all. The ice storm and Erlkoenig represents both the cultural storm and the one that stifles everyone’s emotions and ended in today’s lost snowflakes and dysfunctional culture.

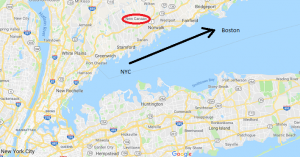

The ice storm is an acerbic, painfully funny description of the decade in limbo between the spaced-out 60s and roaring 80s. When I saw the first act of the play for the first time during the dress rehearsal, it seemed irritating, broken, and lacking in communication. But the second part delivered a self-contained strikingly real, archetypal communication break-down. By chance, I traveled through both time and place in my own life story, that is the I95 and by train from Boston to NYC, and the psychological dimension of the play began to resonate with my experiences.

Rick Moody’s 1994 novel of the same title. Moody’s novel is a clever, witty book operating on many levels – also with drastic language. Sunday Times wrote “This is a blackly funny, beautifully written novel.” True, painfully funny is better word.